Sunday, May 30, 2010

and Phönix. Giving a lecture entitled "Did Turks commit genocide? Confuting the Movie "Ageth" with Armenian Sources" at the Central Office of Union of

European Turkish Democrats (UETD), Dr. Soylemezoglu underscored that both Western and objective Armenian sources show that Armenian genocide allegations

are baseless.

Stating that the documentary "Ageth" includes almost all of the allegations against Turkish people, Soylemezoglu said, "There are about 25 important

allegations against Turks in the documentary. It can be seen that all of those allegations can be refuted refering to Armenian, English, American and

German sources. You do not even need Turkish sources to see that these allegations are baseless."

Stressing that even objective Armenian sources refute the allegations in the movie "Ageth", Soylemezoglu said, "For example, the documentary claims that

Ottoman Armenians did not initiate any rebellion and it is just accusation of Ottomans against Armenians. On the other hand, Armenian sources tell in

detail how Armenians fought against Ottoman forces. They tell how they cooperated with Russian, English and French troops. These facts are even told by

Armenians. English sources also confirm these."

Reminding that so called documentary explained the intention of Ottoman goverment as annihilating Armenian people, Soylemezoglu said, "We learn from

American sources that Ottoman government cooperated with United States to aid Armenian people. There were several American missionaries and American

schools throughout the Ottoman Empire. There were American institutions at 50 different adresses. The Ottoman Empire gave consent to United States for

aiding Armenian people and distributed the donations to Armenian people. If the Ottoman Empire intended to annihilate Armenians, they would not let

American institutions hold such a campaign to aid Armenian's. Would American Institutions in Ottoman Empire not react if they had witnessed massacre of

Armenians? Other than that, the Ottoman Empire provided Armenians money, food and shelter. Would the state help Armenians if it intended to terminate them?

These are all told by American sources in detail."

Stating that tens of thousands people died during forced immigration but the intention was not committing a genocide, Soylemezoglu said, "According to

American, English and Armenian sources, there were more than 1,5 million Armenian's alive in 1919. Armenian population in Ottoman Empire was less than 1,75

million. That means about 250,000 Armenians might have lost their lives during the incidents. These are all told in their own documents. We are guilty that

we do not inform World public on these."

Thursday, June 18, 2009

US diplomat backs proposed commission on Armenian issue

Gordon recalled that he had recently paid visits to Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia since he observed that there are both challenges and opportunities in this region.

“You have two parallel but separate tracks going on; a Turkey-Armenia normalization reconciliation process that we do think is quite potentially historic, where the two countries have agreed on a framework for normalizing their relations. That would include opening the border, which has been closed for far too long, which would establish diplomatic relations and would provide commissions in key areas, including history,” Gordon said. He was apparently referring to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's 2005 letter to then-Armenian President Robert Kocharyan, inviting him to establish a joint commission of historians and experts from both Turkey and Armenia to study the events of 1915 using documents from the archives of Turkey, Armenia and any other country believed to have played a part in the issue.

At a joint press conference in Ankara during Obama's landmark visit to Turkey in early April, President Abdullah Gül recalled the proposal and said: “If it has a high interest in this issue, any country -- for example, it may be the US, it may be France -- can join this joint commission of historians, and we are ready to [face] the results.”

Gordon, meanwhile, also said: “And we encourage that process and we support it. We have said that it is an independent process and believe that it should move forward, regardless of whatever else is happening in Europe or anywhere else, because both countries would benefit. That said, it is nonetheless the case that at the same time negotiations on Nagorno-Karabakh are going on between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and that is part of the context in which the region moves forward. And we're encouraging that process as well. So, again, our view is that these are separate tracks. They're moving forward at different speeds. But we are engaged vigorously on both, because if both were to succeed, it really would be an historic opportunity for the region, from which all three of those countries would benefit.”

Gordon's remarks found a rapid response from the US-based Armenian diaspora. In a press release delivered later the same day, the Armenian National Committee of America (ANCA) said, “The establishment of an Armenia-Turkey commission of historians, a measure Turkey has long sought to cast a doubt over the overwhelming historical record of the Armenian genocide, stands in stark contrast to President Obama's statements during his campaign for the White House.”

18 June 2009, Thursday

TODAY'S ZAMAN ANKARA

http://www.todayszaman.com/tz-web/detaylar.do?load=detay&link=178384&bolum=102

Monday, June 8, 2009

Turkish and Armenian Archives

On the contrary, the Ottoman Imperial Archives is one of the richest in the world and, naturally, the most frequently consulted collection of written sources with regard to the 1915 events. Any research that failed to consult the Turkish State Archives in matters relating to the common histories of Middle and Near East, Balkans, Mediterranean, North Africa, Arabic countries, Caucasus, and beyond, would simply be incomplete. It would be like trying to solve a dispute bwteen two parties by hearing only one of those parties. It would be unfair, incorrect, unscholarly, and unethical.

Turkish State Archives have been brought in line with European Union regulations, which means relevant laws have been amended to enable the same-day-issuance of the research permits. A comprehensive web page (www.devletarsivleri.gov.tr) has been created to include digital copies of classified documents and their translation into contemporary Turkish. Inclusion of English translations of the authentic documents is underway. These initiatives have already resulted in scholars from 80 countries to engage themselves in the archives since 2003. In recent years, everybody from Armenian researchers, to German, Italian and Austrian Historians, to the BBC cameras have had access to research what they liked.

There are approximately 150 million documents that span every period and region of the Ottoman realm in the stacks and vaults of the Ottoman Archives. Each day, new collections in these Ottoman archives are opened to researchers. All these extensive records are well preserved and organized.

Armenians still claim however the archives remain closed...

Prof Dr Stefano Trinchese

Chieti University

Italy

"There is no truth to the claims the Turkish Archives are difficult to access. I went to Istanbul and visited the Turkish Archives. It is true that I faced basic issues initially , but I face similar issues in Italy. In Armenia, I was denied access to the Archives. I wrote a letter but didn’t even get a reply. I tried but never got anywhere."

Prof. Laurenti Barsegian

Genocide Museum Director

Erivan/Armenia

"I have never seen any work by historians, based on the Turkish Archives."

Aras Arafyan

Armenian Historian

England

Has taken copies of thousands of documents both hardcopy and microfilm from the Turkish Archives in Istanbul. (3000 photocopies on the “Armenian Genocide” were taken throughout a 2 year research period.) This fact is documented in the Archive activity logbooks.

Hilmar Keizar

German-American Pro Armenian Historian.

Kaiser has conducted research in more than 60 archives including the Turkish-Ottoman Archives in Istanbul. He has taken photocopies of 5900 documents during his research.

Gegham Manukian

Dashnaktsutyun Party Media Relations

"Why doesn’t Turkey open its archives? We have opened our archives. (???) I have applied many times to no avail and I don’t know of anybody who has accessed the Turkish Archives."

Dr Alexander Safarian

Erivan University

When we refer to archives, we generally mean Historical Archives. I was unable to go to any libraries or Archives in Turkey. I didn’t really want to. I have access to all the documents I need right here in Armenia. I don’t have the will or the want to view Turkish Archives.

TURKEY URGES OPENING OF ARMENIAN ARCHIVE* Turkey, May 21, 2008 (UPI)

-- Turkey has offered $20 million to open an Armenian archive in the United States, claiming documents there will support its version of the 1915 massacre. Yusuf Halacoglu, head of the state-funded Turkish Historical Society, told Hurriyet the archive in Boston includes important documents on the events of 1915. Halacoglu said he had been told the archives cannot be opened because they need proper cataloging. "This would directly open a debate over the genocide claims," he said. "Armenians are aware of this and therefore they are doing their best not to sit at the table." Armenians and most non-Turkish scholars of the period say 1.5 million Armenians were killed by the Ottoman Empire in 1915 and generally label the deaths genocide -- a term the Turkish government disputes. The official Turkish version is that about 300,000 Armenians and 300,000 Turks were killed in an Armenian bid for independence.

The first published catalog of Ottoman archival holdings appeared in 1955 and consisted of ninety pages of archival inventory and commentary. Archivist Attila Çetin followed in 1979 with a more extensive catalog, which is also available in Italian. As the classifying and organizing of the archives continued, the catalog grew. The 1992 edition is 634 pages long. The expanded 1995 compilation provides access to even more documents. Revised editions are to be forthcoming from time to time, as more detailed descriptions become available for the various fonds or individual record groups.

Ottoman archival documentation constitutes an unequaled trove of information about how people lived from the fifteenth through the early twentieth centuries in a territory now comprised of twenty-two nations. İlber Ortaylı, director of the Topkapı Palace Museum at Istanbul, argues that the history of the Ottoman Empire should not be written without Ottoman sources. He is not alone in this. His position is buttressed by a number of specialists in the study of the Ottoman state and society. Albert Hourani, for example, the late British scholar of Middle Eastern affairs, argued that his best advice to history students considering Middle East specialization would be to "learn Ottoman Turkish well and learn also how to use Ottoman documents, since the exploitation of Ottoman archives, located in Istanbul and in smaller cities and towns, is perhaps the most important task of the next generation."

The Archives and the Armenians

There are few comprehensive sources about Armenian life in Anatolia outside of Ottoman archival sources. Diplomatic records, such as those cited by Armenian historian Vahakn Dadrian, as the basis for discussions among genocide scholars are spotty and intertwined with wartime politics. The Ottoman Ministry of the Interior (Dahiliye Nezareti) was the government department directing and supervising the relocation and resettlement of the Armenian population. The collection of the ministry documents covers the period from 1866 to 1922 and consists of 4,598 registers or notebooks. It is classified according to twenty-one subcollections, according to office of origin. Among the available documents in the Ottoman archives are several dozen registers containing the records of the deliberations and actions of the Council of Ministers, which set policies, received reports, and discussed problems that arose regarding the relocations and other wartime events. The minutes of its meetings, deliberations, resolutions, and decisions are bound in 224 volumes covering the years 1885 through 1922. These registers include each and every decree pertaining to the decision to relocate the Ottoman Armenians away from the war zones during World War I. The Records Office of the Sublime Porte (Babıali Evrak Odası) also contains substantial documentation, including the correspondence between the grand vizier and the ministries, as well as the central government and the provinces that can illuminate the events of 1915.

It is ironic, therefore, as politicians seek to deliberate on questions of history, that few historians investigating Armenian issues have actually consulted the Ottoman archives. As Australian historian Jeremy Salt has explained,

The Ottoman archives remain largely unconsulted. When so much is missing from the fundamental source material, no historical narrative can be called complete and no conclusions can be balanced. If the Ottoman sources are properly utilized, the way in which the Armenian question is understood is bound to change.

There is little explanation as to why more historians do not consult the Ottoman archives. They are open to all scholars. Bernard Lewis, Cleveland Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University, who has worked extensively in the Ottoman archives since 1949, has argued that "the Ottoman archives are in the care of a competent and devoted staff who are always willing to place their time and knowledge at the disposal of the visiting scholar, with a personal helpfulness and courtesy that will surprise those with purely Western experience. [These records] are open to all who can read them." The late Stanford Shaw, Professor Emeritus of Turkish and Judeo-Turkish History at the University of California, Los Angeles, also spoke highly of the helpfulness of the archivists. He argued that the sheer amount of new material available removed any excuse for any scholar investigating various nationalist revolts not to spend time examining the new sources.

Even Taner Akçam of University of Minnesota, one of the most vocal proponents of Armenian genocide claims, noted the improvement in the working conditions of the archives. In a recent article, he thanked the staff and especially the deputy director-general of state archives for their help and openness during his last visit. The archivists are now helpful to all researchers, not only those pursuing research which supports the Turkish government's line.

Turkish Military Archives

The archives of the Turkish General Staff Military History and Strategic Studies Directorate in Ankara (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Genelkurmay Askeri Tarih ve Stratejik Etüt Başkanlığı Arşivleri) provide a military perspective. Indeed, more than the Ottoman Archives in the Prime Minister's Office, this repository provides a rich trove of information about internal conditions in the empire, operations of the Ottoman army, and the Special Organization (Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa), somewhat equivalent to the Ottoman special forces, for the period 1914-22.

The World War I and War of Independence archives alone number over five and a half million documents spread among Turkish General Staff Division reports and War Ministry files. Division 1 (Operations) contains military operations plans and orders, operations and situation reports, maps and overlays, general staff orders, mobilization instructions and orders, organizational orders, training and exercise instructions, spot combat reports. Division 2 (Intelligence) contains intelligence estimates and reports and orders of battle. Divisions 3 and 4 (Logistics) contain files concerning procurement, animals, munitions, transportation, rations, and accounting. The Ministry of War files contain the General Command's ciphered cables to military units as well as the papers of the infantry, fortress artillery, and other divisions. Vehip Pasha's Third Army (Erzurum), Jemal Pasha's Fourth Army (Damascus), and Ali İhsan Pasha's Sixth Army (Baghdad) are included among the staff files. These also include the Lightning Armies and Caucasian Armies groups.

Armenian Archives

A full study of the Armenians during World War I should consider material from all sides in a conflict. The Armenian community maintains a number of archives. The archives in Watertown, Massachusetts, contain repositories from the Dashnak Party (Dashnaksutiun, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation) and the First Republic of Armenia. The above, together with the archives of the Armenian patriarchate in Jerusalem and the Catholicosate, the seat of the supreme religious leader of the Armenian people, in Echmiadzin, Armenia, remain closed to non-Armenian researchers. Tatul Sonentz-Papazian, Dashnakist archivist, for example, denied İnönü University scholar Göknur Akçadağ access to the Watertown archives in a June 20, 2008 letter.

Dashnaksutiun archives are also not available to those Armenians who do not tow the party line. Historian Ara Sarafian, director of the Gomidas Institute in London, complained that "some Armenian archives in the diaspora are not open to researchers for a variety of reasons. The most important ones are the Jerusalem Patriarchate archives. I have tried to access them twice and [been] turned away. The other archives are the Zoryan Institute archives, composed of the private papers of Armenian survivors, whose families deposited their records with the Zoryan Institute in the 1980s. As far as I know, these materials are still not cataloged and accessible to scholars."

Beyond the closure of Armenian archives to non-Armenian and even to some Armenian scholars, few of these allow the public to access catalogs detailing their holdings.

Many scholars writing on the Armenian question utilize Britain's National Archives (formerly the Public Record Office) in Kew Gardens. While the British government has made available many of their diplomats' reports for study, much material from the British occupation of Istanbul (1919-22) and elsewhere in Anatolia following World War I remains closed to researchers under the Official Secrets Act and are only partially available in the archives of the government of India in Delhi.

British authorities say they remain sealed for national security reasons. Their release should be important to historians as they will include evidence regarding returning Armenian refugees and other related matters. Files of the British Eastern Mediterranean Special Intelligence Bureau also remain closed, perhaps because the British government does not wish to expose those who may have committed espionage on behalf of Britain. These are important because they should enable historians to research British espionage and sabotage, demoralizing propaganda, and attempts to provoke treason and desertion from Ottoman ranks during and immediately after 1914-18.

The documents of the Secret Office of War Propaganda, which under the direction of Lord James Bryce and Arnold Toynbee developed propaganda used against the Central Powers during World War I, also remain sealed. Their opening will allow historians to assess whether British officials in the heat of war created or exaggerated accounts of deliberate atrocities.

National Archives and the “Armenian Genocide”

Document 141

Dated 23 January 1915. Commander of troops stationed at Kars sent a letter to the Commander of the Russian Caucasus Forces requesting knowledge of:

In the Caucasus, which Armenian Voluntary units and who they are, which regiments they are connected to, and who among these will be located to the properties within Kars. This will allow civil unrest between the citizens and units, murders, robberies, and any type of force will lead to serious disruptions as a lack of discipline and moral amongst them.

FO 371/2485-30439

Dated 6th march 1915 states the Armenians are at the command of the Russians and assisting the French in Adana. The reason for this is to destroy the Ottoman Empire.

Azerbaijan National Archives

Azerbaijan National Archives

The national archives of Azerbaijan detail how the Armenians committed atrocities in the towns of Shamahi, Zengezur, Kuba against Azeri Turks during 1918 – 1919 while under Russian command. What is most important is these documents are written in Russian by Russians.

French Chief of General Staff

Africa Content 64369/11

Dated 2nd October 1916 discloses how the Armenians were being trained by the French Legion in Egypt, Lebanon, and Cyprus so they can fight in Anatolia.

Patrick Devejian

State Minister, France

“Armenians didn’t only escape, but they then joined the French armed forces and fought with the French”

Ottoman Archives

Ottoman Archives

BOA HR SYS 2543/4 Lef 9-10

Dated 2nd February 1919, this document describes Armenians dressed in French Military uniforms killing Turkish Soldiers in Halep.

Russian National Communist Party Archives Central Committee Secret Archives

Document 32

Dated 10 January 1915; The mayor of Iskenderiya sent a letter to the garrison commander. He writes 1200 volunteers had taken up arms, In addition citizens of Iskenderiya numbering 5100 volunteers also had joined. Stating this number can be increased to 10 000 volunteers if needed.

He requests 5100 rifles to be sent from Tiflis for these units.

British Archives and the "Armenian Genocide"

The below are some examples.

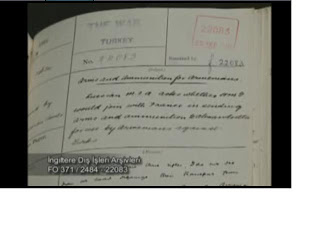

FO 371/284-22083

Dated 23rd February 1915, this document is a copy of a report sent to the Russian Foreign Affairs Minister Sazonov (1910 – 1916) by the Russian Embassy. The report blatantly states the Russians had armed the Armenians in Eastern Anatolia so they can rise against the Turks.

FO 371/25167

Dated 4th March 1915, is an example of a telegraph sent from Bulgaria. It states Bulgarian Armenian Committee member Monsieur Varandian, has gathered a force of 20 000 Armenian Volunteers who want to fight against the Turks and await British assistance to assist them to Iskenderun. Varadian also states there is half this number of volunteers ready to take up arms against the Ottomans in the United States.

Dated 20 March 1915; This document, written on original Armenian Tashnaksutyun Rebel Federation stationary states there are many Armenian volunteer units at the ready.

FO 371/2146-68443

FO 371/2146-68443Dated 7 November 1914 states the Head of the Armenian Delegate Boghus Nubar, who is actually an Ottoman Pasha, states they are ready to fight alongside the Russians the objective being a greater independent Armenia.

FO 371/2146-70404

FO 371/2146-70404Dated 12 Nov 1914, is proof of the planned uprising of the Armenians against their ruling Ottoman Government, and mention of the Armenian Betrayal, labelling the Armenians as Traitors.

FO 371/ 2485-126836

FO 371/ 2485-126836Dated 7th September 1915, a report sent to the British Foreign affairs gives news of an Armenian Captain named “Tarko” who is in preparations for a massacre against the Ottoman Turks, and informs how they have planned with the finest detail.

Planned and Systematic Massacre of the Armenians? You be the Judge.

The picture shows Armenians raiding a mosque at Zeyten, Maras. Note Armenians were not exactly innocent lambs as they try to portray themselves.

DID THE TURKS UNDERTAKE A PLANNED AND SYSTEMATIC MASSACRE OF THE ARMENIANS IN 1915?

One of the Armenians biggest claims is the Ottoman Empire tried to systematically massacre its Armenian population, hence the term "Genocide" is thrown around sparingly by the Armenian Diaspora and those politicians who are under extreme pressure from them.

If a minority within your country spent the last 30 years building up arms, in acts of treason, and deliberatly sided with your enemies during times of war, sent out killing gangs and terrorists to raid your cities and villages; only aim to kill your citizens just becuase they were loyal citizens, taking advantage of your struggle with invading armies, knowing the men of the villages were at the front defending their own country, causing havoc and trouble to affect your military supply lines, destroy your own arsenal of weapons or steal them to use against your own citizens and armies... what would you do?

Even before the war began, in August 1914, the Ottoman leaders met with the Dashnaks at Erzurum in the hope of getting them to support the Ottoman war effort when it came. The Dashnaks promised that if the Ottomans entered the war, they would do their duty as loyal countrymen in the Ottoman armies. However they failed to live up to this promise, since even before this meeting took place, a secret Dashnak Congress held at Erzurum in June 1914 had already decided to use the oncoming war to undertake a general attack against the Ottoman state(25). The Russian Armenians joined the Russian army in preparing an attack on the Ottomans as soon as war was declared. The Catholicos of Echmiadzin assured the Russian General Governor of the Caucasus, Vranzof-Dashkof, that "in return for Russia's forcing the Ottomans to make reforms for the Armenians, all the Russian Armenians would support the Russian war effort without conditions.”(26). The Catholicos subsequently was received at Tiflis by the Czar, whom he told that" The liberation of the Armenians in Anatolia would lead to the establishment of an autonomous Armenia separated from Turkish suzerainty and that this Armenia could be made possible with the protection of Russia. "(27).

Of course the Russians really intended to use the Armenians to annex Eastern Anatolia, but the Catholicos was told nothing about that.

As soon as Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire, the Dashnak Society's official organ Horizon declared:

"The Armenians have taken their place on the side of the Entente states without showing any hesitation whatsoever; they have placed all their forces at the disposition of Russia; and they also are forming volunteer battalions.”(28)

The Dashnak Committee also ordered its cells that had been preparing to revolt within the Ottoman Empire:

"As soon as the Russians have crossed the borders and the Ottoman armies have started to retreat, you should revolt everywhere. The Ottoman armies thus will be placed between two fires: of the Ottoman armies advance against the Russians, on the other hand, their Armenian soldiers should leave their units with their weapons, form bandit forces, and unite with the Russians. "(29) "The Hunchak Committee will use all means to assist the Entente states, devoting all its forces to the struggle to assure victory in Armenia, Cilicia, the Caucasus and Azerbaijan as the ally of the Entente states, and in particular of Russia."(30)

And even the Armenian representative in the Ottoman Parliament for Van, Papazyan, soon turned out to be a leading guerrilla fighter against the Ottomans, publishing a proclamation that:

"The volunteer Armenian regiments in the Caucasus should prepare themselves for battle, serve as advance units for the Russian armies to help them capture the key positions in the districts where the Armenians live, and advance into Anatolia, joining the Armenian units already there. "(31)

As the Russian forces advanced into Ottoman territory in eastern Anatolia, they were led by advanced units composed of volunteer Ottoman and Russian Armenians, who were joined by the Armenians who deserted the Ottoman armies and went to fight on the Russians side. Many of these also formed bandit forces with weapons and ammunition which they had for years been stocking in Armenian and missionary churches and schools, going on to raid Ottoman supply depots both to increase their own arms and to deny them to the Ottoman army as it moved to meet this massive Russian invasion. Within a few months after the war began, these Armenian guerrilla forces, operating in close coordination with the Russians, were savagely attacking Turkish cities, towns and villages in the East; massacring their inhabitants without mercy, while at the same time working to sabotage the Ottoman army's war effort by destroying roads and bridges, raiding caravans, and doing whatever else they could to ease the Russian occupation. The atrocities committed by the Armenian volunteer forces accompanying the Russian army were so severe that the Russian commanders themselves were compelled to withdraw them from the fighting fronts and send them to rear guard duties. The memoirs of all too many Russian officers who served in the East at this time are filled with accounts of the revolting atrocities committed by these Armenian guerrillas, which were savage even by the relatively primitive standards of war then observed in such areas.(32)

These Armenian atrocities didnt only affect Turks and other Muslims. The Armenian guerrillas had never been happy with the failure of the Greeks and Jews to fully support their revolutionary programs. As a result in Trabzon and vicinity they massacred thousands of Greeks, while in the area of Hakkari it was the Jews who were rounded up and massacred by the Armenian guerrillas (33). Basically the aim of these atrocities was to leave only Armenians in the territories being claimed for the new Armenian state; all others therefore were massacred or forced to flee for their lives so as to secure the desired Armenian majority of the population in preparation for the peace settlement.

Leading the first Armenian units who crossed the Ottoman border in the company of the Russian invaders was the former Ottoman Parliamentary representative for Erzurum, Karekin Pastirmaciyan, who now assumed the revolutionary name Atmen Garo. Another former Ottoman parliamentarian, Hamparsum Boyaciyan, led the Armenian guerrilla forces who ravaged Turkish villages behind the lines under the nickname "Murad", specifically ordering that" Turkish children also should be killed as they form a danger to the Armenian nation." Another former Member of Parliament, Papazyan, led the Armenian guerrilla forces that ravaged the areas of Van, Bitlis and Mush.

In March 1915 the Russian forces began to move toward Van. Immediately, on April 11, 1915 the Armenians of Van began a general revolt, massacring all the Turks in the vicinity so as to make possible its quick and easy conquest by the Russians. Little wonder that Czar Nicho1as II sent a telegram of thanks to the Armenian Revolutionary Committee of Van on April 21, 1915, "thanking it for its services to Russia." The Armenian newspaper Gochnak, published in the United States, also proudly reported on May 24, 1915 that "only, 1,500 Turks remain in Van", the rest having been slaughtered.

The Dashnak representative told the Armenian National Congress assembled at Tiflis in February 1915 that "Russia provided 242,000 rebels before the war even began to arm and prepare the Ottoman Armenians to undertake revolts", giving some idea of how the Russian -Armenian alliance had long prepared to undermine the Ottoman war effort (34). Under these circumstances, with the Russians advancing along a wide front in the East, with the Armenian guerrillas spreading death and destruction while at the same time attacking the Ottoman armies from the rear, with the Allies also invading the Empire along a wide front from Galicia to Iraq, the Ottoman decision to deport Armenians from the war areas was a moderate and entirely legitimate measure of self defence.

Even after the revolt and massacres at Van, the Ottoman government made one final fort to secure general Armenian support for the war effort, summoning the Patriarch, some Armenian Members of Parliament, and other delegates to a meeting where they were warned drastic measures would be taken unless Armenians stopped slaughtering Muslims and working to undermine the war effort. When there was no evident lessening of the Armenian attacks, the government finally acted. On April 24, 1915 the Armenian revolutionary committees were closed and 235 of their leaders were arrested for activities against the state. It’s the date of these arrests that in recent years has been annually commemorated by Armenian Nationalist groups throughout the world in commemoration of the "massacre" that they claim took place at this time. (Note that of all the 235 Armenians arrested for treason on April 24 1915 all 235 were admitted to Prisons in Ankara and Istanbul.) No such massacre, however, took place, at this or any other time during e war: In the face of the great dangers which the Empire faced at that time, great care was taken to make certain that the Armenians were treated carefully and compassionately as they ere deported, generally to Syria and Palestine when they came from southern Anatolia, and Iraq if they came from the north. The Ottoman Council of Ministers thus ordered:

"When those of the Armenians resident in the aforementioned towns and villages who have to be moved are transferred to their places of settlement and are on the road, their comfort must be assured and their lives and property protected; after their arrival their food should be paid for out of Refugees' Appropriations until they are definitively settled in their new homes. Property and land should be distributed to them in accordance with their previous financial situation as well as their current needs; and for those among them needing further help, the government should build houses, provide cultivators and artisans with seed, tools, and equipment. "(35)

"This order is entirely intended against the extension of the Armenian Revolutionary Committees; therefore do not execute it in such a manner that might cause the mutual massacre of Muslims and Armenians." "Make arrangements for special officials to accompany the groups of Armenians who are being relocated, and make sure they are provided with food and other needed things, paying the cost out of the allotments set aside for emigrants. "(36)

"The food needed by the emigrants while travelling until they reach their destinations must be provided ... for poor emigrants by credit for the installation of the emigrants. The camps provided for transported persons should be kept under regular supervision; necessary steps for their well being should be taken, and order and security assured. Make certain that indigent emigrants are given enough food and that their health is assured by daily visits by a doctor. .. Sick people, poor people, women and children should be sent by rail and others on mules, in carts or on foot according to their power of endurance. Each convoy should be accompanied by a detachment of guards, and the food supply for each convoy should be guarded until the destination is reached ... In cases where the emigrants are attacked, either in the camps or during the journeys, all efforts should be taken to repel the attacks immediately ..."(37)

Out of some 700,000 Armenians who were transported in this way until early 1917, certainly some lives were lost, as the result both of large scale military and bandit activities then going on in the areas through which they passed, as well as the general insecurity and blood feuds which some tribal forces sought to carry out as the caravans passed through their territories. The Armenians had spent no time in killing Ottoman Subjects who were not in favour of their cause, as such many Kurdish tribes were attacked and killed. The Kurds took this as an opportunity to seek revenge. In addition, the deportations and settlement of the deported Armenians took place at a time when the Empire was suffering from severe shortages of fuel, food, medicine and other supplies; as well as large-scale plague and famine. It should not be forgotten that, at the same time, an entire Ottoman army of 90,000 men was lost in the East as a result of severe shortages or that through the remainder of the war as many as three or four million Ottoman subjects of all religions died as a result of the same conditions that afflicted the deportees. How tragic and unfeeling it is, therefore, for Armenian nationalists to blame the undoubted suffering of the Armenians during the war to something more than the same anarchical conditions which afflicted all the Sultan's subjects. This is the truth behind the false claims distorting historical facts by ill-devised mottoes such as the ''first genocide of the twentieth century" which Armenian propagandists and terror groups try to revive to justify the same tactics of terror today which brought such horrors to the Ottoman Empire during the last century.

(24) NALBANDIAN, Louise, op. cit., p.11 I.

(25) Aspirations et Agissements Revolutionnaires des Comites Armeniens avant et apres la Proclamation de la Constitution Ottomane, Istanbul, 1917, pp.144 -146.

(26) TCHALKOUCHIAN, Gr., Le Livre Rouge, Paris, 1919, p.12.

(27) TCHALKOUCHIAN, Gr., op. cit.

(28) URAS, Esat, op. cit., p. 594.

(29) HOCAOGLU, Mehmed, Tarihte Ermeni Mezalimi ve Ermeniler, Istanbul, 1976, pp. 570-571

(30) Aspirations et Agissements revolutionnaires des Comites Armeniens, pp.151-153.

(31) URAS, Esat, op. cit., pp. 5% - 600.

(32 ) Journal de Guerre du Deuxieme Regiment d'Artillerie de Forteresse Russe d'Erzeroum, 1919.

(33) SCHEMSI, Kara, op. cit., p. 41 and p. 49.

(34) URAS, Esat, op. cit., p. 604.

(35)Council of Ministers Decrees, Prime Ministry's Archives, Istanbul, Volume 198, Decree 1331/163, May 1915.

(36)British Foreign Office Archives, Public Record Office, 37119158/E 5523.

Wednesday, June 3, 2009

U.S.-Turkish Relationship ‘Exceptionally Strong,’ Mullen Says

http://elitestv.com/pub/2009/06/us-turkish-relationship-exceptionally-strong-mullen-says

| ||

Sunday, May 31, 2009

Did the Turks really try to masacre the Armenians? Some facts to consider...

Pictured is an Armenian Tashnak terrorist gang who no doubt killed many Muslim woman and children during those years.

The so-called "Armenian Question" is generally thought of as having begun in the second half of the nineteenth century. One can easily point to the Russo- Turkish war (1877-78) and the Congress of Berlin (1878) which concluded the war as marking the emergence of this question as a problem in

The Russians were not the only foreign power seeking to protect the Ottoman Christians.

On the other hand, the Reform Proclamation of 1856 was of major importance. While not abolishing the separate millets and churches and the institutions that they supported, the Ottoman government now provided equal rights for all subjects regardless of their religion, in the process seeking to eliminate all special privileges and distinctions based on religion, and requiring the millets to reconstitute their internal regulations in order to achieve these goals. Insofar as the Armenians were concerned, the result was the Armenian Millet Regulation, drawn up by the Patriarchate and put into force by the Ottoman government on 29 March 1862. Of particular importance the new regulation placed the Armenian millet under the government of a council of 140 members, including only 20 churchmen from the Istanbul Patriarchate, while 80 secular representatives were to be chosen from the

It was against this background that the Ottoman-Russian war (1877 - 78) awakened Armenian dreams for independence with Russian help and under Russian guidance. Toward the end of the war, the Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul, Nerses Varjabedian, got in touch with the Russian Czar with the help of the Catholicos of Echmiadzin, asking

(1) URAS, Esat, Op. Cit. pp 212 - 215

The Treaty of San Stephano did not, however, constitute the final settlement of the Russo-Turkish war. Britain rightly feared that its provisions for a Greater Armenia in the East would inevitably not only establish Russian hegemony in those areas but also, and even more dangerous, in the Ottoman Empire, and through "Greater Armenia" to the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, where they could easily threaten the British possessions in India. In return for an Ottoman agreement for British occupation of

A committee sent by the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul attended the Congress of Berlin, but it was so unhappy at the final treaty and the Powers' failure to accept its demands that it returned to

(2) URAS, Esat, op. cit., pp 250 - 251

It had been British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli and the Tories who had defended Ottoman integrity against Russian expansion at the Congress of Berlin. But with the assumption of power by William E. Gladstone and the Liberals in 1880, British policy toward the Ottomans changed drastically to one which sought to protect British interests by breaking up the Ottoman Empire and creating friendly small states under British influence in its place, one of which was to be

"Gladstone is organizing the dissatisfied Armenians, putting them under discipline and promising them assistance, settling many of them in

Edgar Granville commented that

"There was no Armenian movement in Ottoman territory before the Russians stirred them up. Innocent people are going to be hurt because of this dream of a Greater

The Armenian writer Kaprielian declared proudly in his book The Armenian Crisis and Rebirth that "the revolutionary promises and inspirations were owed to

(3) SCHEMSI, Kara, op. cit. pp 20 - 21

In pursuit of these policies, starting in 1880 a number of Armenian revolutionary societies was established in Eastern Anatolia, the Black Cross and Armenian societies in Van and the National Guards in

According to Louise Nalbandian, a leading Armenian researcher into Armenian propaganda, the Hunchak program stated that:

"Agitation and terror were needed to "elevate the spirit" of the people. The people were also to be incited against their enemies and were to "profit" from retaliatory actions of these same enemies. Terror was to be used as a method of protecting the people and winning their confidence in the Hunchak program. The party aimed at terrorizing the Ottoman government, thus contributing toward lowering the prestige of that regime and woorking toward its complete disintegration. The government itself was not to be the only focus of terroristic tactics. The Hunchaks wanted to annihilate the most dangerous of the Armenian and Turkish individuals who were then working for the government as well as to destroy all spies and informers. To assist them in carrying out all of these terroristic acts, the party was to organize an exclusive branch specifically devoted to performing acts of terrorism. The most opportune time to institute the general rebellion for carrying out immediate objectives was when

KS Papazian wrote of the Dashnak Society:

“The purpose of the A. R. Federation (Dashnak) is to achieve political and economic freedom in Turkish

One of the Dashnak founders and idealogists, Dr Jean Loris-Melikoff wrote:

'The truth is that the party (Dashnak Committee) was ruled by an oligarchy, for whom the particular interests of the party came before the interests of the people and nation ... They (the Dashnaks) made collections among the bourgeoisie and the great merchants. At the end, when these means were exhausted, they resorted to terrorism, after the teachings of the Russian revolutionaries that the end justifies the means. "(6)

(4)NALBANDIAN, Louise, Armenian Revolutionary Movement,

(5) PAPAZIAN, K. S Patriotism Perverted,

(6) LORIS-MELIKOFF, Dr. Jean la Revolution Russe et les Nouvelles Republiques Transcaucasiennes,

Thus as Armenian writers themselves have freely admitted, the goal of their revolutionary societies was to stir revolution, and their method was terror. They lost no time in putting their programs into operation, stirring a number of revolt efforts within a short time, with the Hunches taking the lead at first, and then the Dashnaks following, planning and organizing their efforts outside the Ottoman Empire before carrying them out within the boundaries of the Sultan's dominions.

The first revolt came at Erzurum in 1890. It was followed by the Kumkapl riots in Istanbul the same year, and then risings in Kayseri, Yozgat, Corum and Merzifon in 1892 1893, in Sasun in 1894, the Zeytun revolt and the Armenian raid on the Sublime Porte in 1895, the Van revolt and occupation of the Ottoman Bank in Istanbul in 1896, the Second Sasun revolt in 1903, the attempted assassination of Sultan Abdulhamid II in 1905, and the Adana revolt in 1909. All these revolts and riots were presented by the Armenian revolutionary societies in Europe and America as the killing of Armenians by Turks, and with this sort of propaganda message they stirred considerable emotion among Christian peoples. The missionaries and consular representatives sent by the Powers to Anatolia played major roles in spreading this propaganda in the western press, thus carrying out the aims of the western powers to turn public opinion against Muslims and Turks to gain the necessary support to break up the Ottoman Empire.

There were many honest western diplomatic and consular representatives who reported what actually was happening, that it was the Armenian revolutionary societies that were doing the revolting and slaughtering and massacring to secure European intervention in their behalf.

In 1876, the British Ambassador in Istanbul reported that the Armenian Patriarch had said to him:

"If revolution is necessary to attract the attention and intervention of Europe, it would not be hard to do so."(7)

On 28 March 1894 the British Ambassador in Istanbul, Currie reported to the Foreign Office:

"The aim of the Armenian revolutionaries is to stir disturbances, to get the Ottomans to react to violence, and thus get the foreign Powers to intervene." (8)

On 28 January 1895 the British Consul in Erzurum, Graves reported to the British Ambassador in Istanbul:

"The aims of the revolutionary committees are to stir up general discontent and to get the Turkish government and people to react with violence, thus attracting the attention of the foreign powers to the imagined sufferings of the Armenian people, and getting them to act to correct the situation. "(9)

"If no Armenian revolutionary had come to this country, if they had not stirred Armenian revolution, would these clashes have occurred ", answering "Of course not. I doubt if a single Armenian would have been killed. "(10)

"The Dashnaks and Hunchaks have terrorized their own countrymen, they have stirred up the Muslim people with their thefts and insanities, and have paralyzed all efforts made to carry out reforms; all the events that have taken place in Anatolia are the responsibility of the crimes committed by the Armenian revolutionary committees. "(11)

British Consul General in Adana, Doughty Wily, wrote in 1909:

“The Armenians are working to secure foreign intervention.” (12)

"In 1895 and 1896 the Armenian revolutionary committees created such suspicion between the Armenians and the native population that it became impossible to implement any sort of reform in these districts. The Armenian priests paid no attention to religious education, but instead concentrated on spreading nationalist ideas, which were affixed to the walls of monasteries, and in place of performing their religious duties they concentrated on stirring Christian enmity against Muslims. The revolts that took place in many provinces of Turkey during 1895 and 1896 were caused neither by any great poverty among the Armenian villages nor because of Muslim attacks against them. In fact these villagers were considerably richer and more prosperous than their neighbors. Rather, the Armenian revolts came from three causes:

1. Their increasing maturity in political subjects;

2. The spread of ideas of nationality, liberation, and independence within the Armenian community;

3. Support of these ideas by the western governments and their encouragement through the efforts of the Armenian priests. "(13)

"The Dashnak revolutionary society is working to stir up a situation in which Muslims and Armenians will attack each other, and to thus pave the way for Russian intervention. "(14)

(7) URAS, Esat; op. cit., p.188.

(8) British Blue Book, NI. 6 (1894), p. S7.

(9) British Blue Book, Nr. 6 (1894), pp. 222 - 223.

(10)URAS, Esat, op. cit., p. 426.

(11) British Blue Book, Nr. 8 (1896), p.l 08.

(12)SCHEMSI, Kara, op. cit., p.ll.

Finally, the Dashnak ideologue Varandian admits that the society "wanted to assure European intervention, "(15) while Papazian stated that "the aims of their revolts was to assure that the European powers would mix into “ottoman internal affairs.” (16). At each of their armed revolts the Armenian terrorist committees have always propagated that European intervention would immediately follow. Even some of the committee members believed in this propaganda. In fact, during the occupation of the Ottoman Bank in Istanbul the Armenian terrorist Armen Aknomi committed suicide after having waited in desperation the arrival of the British fleet. It can be seen thus that the basis for the Armenian revolts was not poverty, nor was it oppression or the desire for reform; rather, it was simply the result of a joint effort on the part of the Armenian revolutionary committees and the Armenian church, in conjunction with the Western Powers and Russia, to provide the basis to break up the Ottoman Empire.

(13) General MA YEWSKI, Statistique d_es Provinces de Van et de Bitlis, pp.lI-13, Petersburg, 1916.

(14) SCHEMSI, Kara, op. cit., p.1 1.

(15) VARANDIAN, Mikayel, History of the Dashnagtzoutune, Paris, 1932, p. 302.

(16) PAPAZIAN, K. S., op. cit., p.19.

In reaction to these revolts, the Ottomans did what other states did in such circumstances, sending armed forces against the rebels to restore order, and for the most part succeeding quickly since very few of the Armenian populace supported or helped the rebels or the revolutionary societies. However for the press and public of Europe, stirred by tales spread by the missionaries and the revolutionary societies themselves, every Ottoman restoration of order was automatically considered a "massacre" of Christians, with the thousands of slaughtered Muslims being ignored and Christian claims against Muslims automatically accepted. In many cases, the European states not only intervened to prevent the Ottomans from restoring order, but also secured the release of many captured terrorists, including those involved in the Zeytun revolt, the occupation of the Ottoman Bank, and the attempted assassination of Sultan Abdulhamid. While most of these were expelled from the Ottoman Empire, with the cooperation of their European sponsors, it did not take long for them to secure forged passports and other documents and to return to Ottoman territory to resume their terroristic activities. Whatever were the claims of the Armenian revolutionary societies and whatever the ambitions of the imperial powers of Europe, there was one major fact which they simply could not ignore. The Armenians comprised a very small minority of the population in the territories being claimed in their name, namely the six eastern districts claimed as "historic Armenia” (Erzurum, Bitlis, Van, Elaziz, Diyarbaklr and Sivas), the two provinces claimed to comprose ''Armenian Cilicia" (Aleppo and Adana) and finally Trabzon which was later claimed to have an outlet to the Black Sea coast. Even the French Yellow Book, which among western sources made the largest Armenian population claims, still showed them in a sizeable minority. (Approximately 16.6% of population in Erzurum, Bitlis, Van, Elaziz, Diyarbakir, Sivas, Adana, Aleppo, Trabzon were Armenian)

Thus even by these extreme claims, the Armenians still constituted no more than one third of the provinces population. According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica of 1910, the Armenians were only 15 percent of the area's population as a whole, making it very unlikely that they could in fact achieve independence in any part of the Ottoman Empire without the massive foreign assistance that would have been required to push out the Turkish majorities and replace them with Armenian emigrants.

Russia in fact was only using the Armenians for its own ends. It had no real intention of establishing Armenian independence, either within its own dominions or in Ottoman territory. Almost as soon as the Russians took over the Caucasus, they adopted a policy of Russifiying the Armenians as well as establishing their own control over the Armenian Gregorian church in their territory. By virtue of the Polijenia Law of 1836, the powers and duties of the Catholicos of Etchmiadzin were restricted, while his appointment was to be madeby the Czar. In 1882 all Armenian newspapers and schools in the Russian Empire were closed, and in 1903 the state took direct control of all the financial resources of the Armenian Church as well as Armenian establishments and schools. At the same time Russian Foreign Minister Lobanov-Rostowsky adopted his famous goal of "An Armenia without Armenians", a slogan which has been deliberately attributed to the Ottoman administration by some Armenian propagandists and writers in recent years. Whatever the reason, Russian oppression of the Armenians was severe. The Armenian historian Vartanian relates in his History of the Armenian Movement that "Ottoman Armenia was completely free in its traditions, religion, culture and language in comparison to Russian Armenia under the Czars."

Edgar Granville writes, "The Ottoman Empire was the Armenians' only shelter against Russian oppression."

That Russian intentions were to use the Armenians to annex Eastern Anatolia and not to create an independent Armenia is shown by what happened during World War 1. In the secret agreements made among the Entente powers to divide the Ottoman Empire, the territory which the Russians had promised to the Armenians as an autonomous or independent territory was summarily divided between Russia and France without any mention of the Armenians, while the Czar replied to the protests of the Catholicos of Etchmiadzin only that "Russia has no Armenian problem." The Armenian writer Borian thus concludes:

"Czarist Russia at no time wanted to assure Armenian autonomy. For this reason one must consider the Armenians who were working for Armenian autonomy as no more than agents of the Czar to attach Eastern Anatolia to Russia. "

The Russians thus have deceived the Armenians for years; and as a result the Armenians have been left with nothing more than an empty dream.

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x6p5p3_hey-obama-do-you-like-to-move-ity-h

Saturday, May 30, 2009

HAVE THE TURKS ALWAYS ATTACKED AND MISRULED ARMENIANS THROUGHOUT HISTORY?

The evidence of history overwhelmingly denies these claims. We already have seen that the contemporary Armenian historians themselves related how the Armenians of Byzantium welcomed the Seljuk conquest with celebrations and thanksgivings to God for having rescued them from Byzantine oppression. The Seljuks gave protection to an Armenian church which the Byzantines had been trying to destroy. They abolished the oppressive taxes which the Byzantines had imposed on the Armenian churches, monasteries and priests, and in fact exempted such religious institutions from all taxes. The Armenian community was left free to conduct its internal affairs in its own way, including religious activities and deducation, and there never was any time at which Armenians or other non-Muslims were compelled to convert to Islam. The Armenian spiritual leaders in fact went to Seljuk Sultan Melikshah (Pictured) to thank him for this protection. The Armenian historian Mathias of Edessa relates that,

"Melikshah's heart is full of affection and goodwill for Christians; he has treated the sons of Jesus Christ very well, and he has given the Armenian people affluence, peace, and happiness. "(3)

"Kilich Arslan's death has driven Christians into mourning since he was a charitable person of high character. "

How well the Seljuk Turks treated the Armenians is shown by the fact that some Armenian noble families like the Tashirk family accepted Islam of their own free will and joined the Turks in fighting Byzantium.

Turkish tradition and Muslim law dictated that non-Muslims should be well treated in Turkish and Muslim empires. The conquering Turks therefore made agreements with their non-Muslim subjects by which the latter accepted the status of zhimmi, agreeing to keep order and pay taxes in return for protection of their rights and traditions. People from different religions were treated with an unprecedented tolerance which was reflected into the philosophies based on goodwill and human values cherished by great philosophers in this era such as Yunus Emre and Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi who are well-known in the Islamic world with their benevolent mottoes such as "having the same view for all 72 different nations" and "you will be welcome whoever you are, and whatever you believe in". This was in stark contrast to the terrible treatment which Christian rulers and conquerors often have meted out to Christians of other sects, let alone non-Christians such as Muslims and Jews, as for example the Byzantine persecution of the Armenian Gregorians, Venetian persecution of the Greek Orthodox inhabitants of the Morea and the Aegean islands, and Hungarian persecution of the Bogomils.

The establishment and expansion of the Ottoman Empire, and in particular the destruction of Byzantium following Fatih Mehmed's conquest of Istanbul in 1453 opened a new era of religious, political, social, economic and cultural prosperity for the Armenians as well as the other non-Muslim and Muslim peoples of the new state. The very first Ottoman ruler, Osman Bey (1300-1326), permitted the Armenians to establish their first religious center in western Anatolia, at Kutahya, to protect them from Byzantine oppression. This center subsequently was moved, along with the Ottoman capital, first to Bursa in 1326 and then to Istanbul in 1461, with Fatih Mehmet issuing a ferman definitively establishing the Armenian Patriarchate there under Patriarch Hovakim and his successors(4). As a result, thousands of Armenians emigrated to Istanbul from Iran, the Caucasus, eastern and central Anatolia, the Balkans and the Crimea, not because of force or persecution, but because the great Ottoman conqueror had made his empire into a true center of Armenian life. The Armenian community and church thus expanded and prospered as parts of the expansion and prosperity of the Ottoman Empire.

The Gregorian Armenians of the Ottoman Empire, like the other major religious groups, were organized into millet communities under their own religious leaders. Thus the ferman issued by Fatih Mehmet establishing the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul specified that the Patriarch was not only the religious leader of the Armenians, but also their secular leader. The Armenians had the same rights as Muslims, but they also had certain special privileges, most important among which was exemption from military service. Armenians and other nonMuslims generally paid the same taxes as Muslims, with the exception of the Poll Tax (Harach or Jizye), which was imposed on them in place of the state taxes based particularly on Muslim religious law, the Alms Tax (Zakat) and the Tithe (Osur), from which non-Muslims were exempted. The Armenian millet religious leaders themselves assessed and collected the Poll Taxes from their followers and turned the collections over to the Treasury officials of the state.

The Armenians were allowed to establish religious foundations (vakif) to provide financial support for their religious, cultural, educational and charity activities, and when needed the Ottoman state treasury gave additional financial assistance to the Armenian institutions which carried out these activities as well as to the Armenian Patriarchate itself. These Armenian foundations remain in operation to the present day in the Turkish Republic, providing substantial financial support to the operations of the Armenian church.

By Ottoman law all Christian subjects who were not Greek Orthodox were included in the Armenian Gregorian millet. Thus the Paulicians and Yakubites in Anatolia as well as the Bogomils and Gypsies in the Balkans were counted as Armenians, leading to substantial disputes in later times as to the total number of Armenians actually living in the Empire.

The Armenian community expanded and prospered as a result of the freedom granted by the sultans. At the same time Armenians shared, and contributed to, the Turkish-Ottoman culture and ways of life and government to such an extent that they earned the particular trust and confidence of the sultans over the centuries, gaining the attribute "the loyal millet". Ottoman Armenians became extremely wealthy bankers, merchants, and industrialists, while many at the same time rose to high positions in governmental service. In the 19th century, for example, twenty-nine Armenians achieved the highest governmental rank of Pasha. There were twenty-two Armenian ministers, including the Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Finance, Trade and Post, with other Armenians making major contributions to the departments concerned with agriculture, economic development, and the census. There also were thirty-three Armenian representatives appointed and elected to the Parliaments formed after 1826, seven ambassadors, eleven consul-generals and consuls, eleven university professors, and forty-one other officials of high rank.(Facts from the Turkish Armeniens, Jamanak, Istanbul, 1980, p. 4 et KO(:AS, Sadi; Tarih Boyunca Ermeniler ve TtirkErmeni Iliskileri, Ankara, 1967, pp. 92 -115. )

Over the centuries Armenians also made major contributions to Ottoman Turkish art, culture and music, producing many artists of first rank who are objects of praise and sources of pride for Turks as well as Armenians in Turkey. The first Armenian printing press was established in the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century.

Thus the Armenians and Turks, and all the various races of the Empire lived in peace and mutual trust over the centuries, with no serious complaints being made against the Ottoman system or administration which made such a situation possible. It is true that, from time to time, internal difficulties did arise within some of the individual millets. Within the Armenian millet disputes arose over the election of the patriarch between the "native" Armenians, who had come to Istanbul from Anatolia and the Crimea, and those called "eastern" or "foreign" Armenians, who came from Iran and the Caucasus. These groups often complained against each other to the Ottomans, trying to gain governmental support for their own candidates and interests, and at the same time complaining about the Ottomans whenever the decisions went against them, despite the long-standing Ottoman insistence on maintaining strict neutrality between the groups. The gradual triumph of the "easterners" led to the appointment of nonreligious individuals as Patriarchs, to corruption and misrule within the Armenian millet, and to bloody clashes among conflicting political groups, against which the Ottomans were forced to intervene to prevent the Armenians from annihilating each other.

These internal disputes, as well as the general decline of religious standards within the Gregorian millet led many Armenians to accept the teachings of foreign Catholic and Protestant missionaries sent into the Empire during the 19th century, causing the creation of separate millets for them later in the century. The Armenian Gregorian leaders asked the Ottoman government to intervene and prevent such conversions, but the Ottomans refrained from doing so on the grounds that it was an internal problem which had to be dealt with by the millet and not the state. Bloody clashes followed, with the Gregorian patriarchs Chuhajian and Tahtajian going so far to excommunicate and banish all Armenian protestants(5). Later on, serious clashes also emerged among the Armenian Catholics as to the nature of their relationship with the Pope, with the latter excommunicating all those who did not accept his supremacy, forcing the Ottomans finally to intervene and reconcile the two Catholic groups in 1888.

The freedom granted and the great tolerance shown by the Ottomans to non-Muslims was so well known throughout Europe that the empire of the sultans became a major place of refuge for those fleeing from religious and political persecution. Starting with the thousands of Jews who fled from persecution in Spain following its re-conquest in 1492, Jews fled to the Ottoman Empire from the regular pogroms to which they were subjected in Central and East Europe and Russia. Catholics and Protestants likewise fled to the Ottoman Empire, often entering the service of the sultans and making major contributions to Ottoman military and governmental life. Many of the political refugees from the reaction that followed the 1848 revolutions in Europe also fled for protection to the Ottoman Empire.

The claims that the Ottomans misruled non-Muslims in general and the Armenians in particular thus are disproved by history, as attested by major western historians, from the Armenians Asoghik and Mathias to Voltaire, Lamartine, Claude Farrere, Pierre Loti, Nogueres Ilone Caetani, Philip Marshall Brown, Michelet, Sir Charles Wilson, Politis, Arnold, Bronsart, Roux, Grousset Edgar Granville Gamier, Toynbee, Bernard Lewis, Shaw, Price, Lewis Thomas, Bombaci and others, some of whom could certainly not be labelled as pro-turkish. To cite but a few of them:

"The great Turk is governing in peace twenty nations from different religions. Turks have taught to Christians how to be moderate in peace and gentle in victory. "

"Despite the great victory they won, Turks have generously granted to the people in the conquered regions the right to administer themselves according to their own rules and traditions."

Politis who was the Foreign Minister in the Greek Government led by Prime Minister Venizelos:

"The rights and interests of the Greeks in Turkey could not be better protected by any other power but the Turks."

"It is an undeniable historic fact that the Turkish armies have never interfered in the religious and cultural affairs in the areas they conquered. "

"Unless they are forced, Turks are the world's most tolerant people towards those of other religions:"

Even when Napoleon Bonaparte sought to stir a revolt among the Armenian Catholics of Palestine and Syria to support his invasion in 1798-1799, his Ambassador in Istanbul General Sebastiani replied that "The Armenians are so content with their lives here that this is impossible. "

(3) MATHIAS of EDDESSA, Chronicles, Nr. 129

(4) URAS, Esat, Tarihte Ermeniler ve Ermeni Meselesi, 2nd Edition, Istanbul 1976, p. 149

(5) SCHEMSI, Kara Turcs et Armeniens devant l"Historie, Geneve, Imprimerie Nationale, 1919, p.19